Certain Python functions should not be used or should be used only with caution. Python’s documentation typically includes a note about the dangers but does not always fully illustrate why the function is risky. We will discuss a few dangerous categories of Python functions and some alternatives. If you see these used in the wild, it may not be bad but we should pay close attention to their usage.

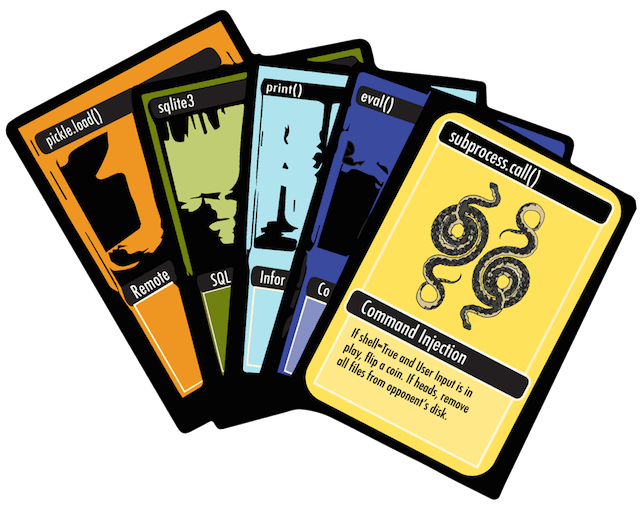

Illustration by Carissa Sandoval

Illustration by Carissa Sandoval

The Command Injection Series

The first group of dangerous Python functions revolve around trusting user-provided input and piping it into a shell.

Why they’re useful

Sometimes you need to send a command-line application and it’s convenient to do

that using Python’s subprocess module using

subprocess.call() and

setting shell=True.

os.system() and

os.popen*() have been

deprecated since Python 2.6 in favor of the subprocess module. They have

a simple API and they’ve been around for a while so you may run into them in

older applications.

Why they’re dangerous

Using shell=True (or any of the similar command-line oriented tools in os),

can expose you to security risks if someone crafts input to

issue different commands than the ones you intended.

A dangerous example

Let’s say we want to write a function to transcode a user-specified video file into a different format. We ask the user where to find the file on disk and then run it through ffmpeg to transcode it. What could go wrong?

import subprocess

def transcode_file():

filename = raw_input('Please provide the path for the file to transcode: ')

command = 'ffmpeg -i "{source}" output_file.mpg'.format(source=filename)

subprocess.call(command, shell=True) # a bad idea!What if someone provides a file with a name like "; rm -rf /? If the host

machine runs the Python process as a privileged user, that could delete all

of the files on the machine. That’s bad.

What to use instead

subprocess with shell=False. It protects you against most of the risk

associated with piping commands to the shell. If you go this route,

shlex.split()

makes it easier to prepare the command (and is what the Python docs recommend).

sh - Useful for issuing commands to other

applications. I had some trouble issuing complex commands through sh before

because of the way it quotes variables. That said, if it works for your use

case, then go for it!

If you must use them…

Escape your variables! You can use

pipes.quote() for

that if you’re using Python 2.x or

shlex.quote()

if you’re using Python 3.3 or newer.

Additional references

- Subprocess documentation on security implications

- OWASP Command Injection

- Shellshock affects os.popen

- PEP 324 - Subprocess

Code Injection - exec, eval

The second group of dangerous functions relate to taking input and interpreting it as Python code.

Why they’re useful

exec() and

eval() take strings

and turn them into executable code. They can be useful, especially if you are

the one who controls the input. As one example, I’ve used eval before

to evaluate a large dict-like string into a dictionary.

Why they’re dangerous

Again, we do not know what the user will provide in all cases. eval() and

exec() will execute we feed them. A user could build a string so that it runs

other Python functions to potentially erase all your data, expose your secret

keys, dump your database, or perform other malicious actions.

A dangerous example

Related to the previous example, suppose you’re evaling a string that looks

like this: "os.system('rm -rf /') # dangerous!". It, too, could erase all

your files.

What to use instead

It depends. If you’re trying to use eval or exec,

there may be a better way to accomplish what you’re trying to do.

The functions can be used in many different ways so it is challenging to provide

an alternative that covers all use cases.

If you’re using them to perform serialization / deserialization, it would

probably be better to use another format, such as JSON, which can be loaded

with the json module.

If you must use them…

Again, escape your input. You can also disable the built-ins to make it harder to craft malicious input, which Ned Batchelder covers in Eval really is dangerous.

Additional references

Next time…

We’ve covered ways in which user input can pose serious risks to Python applications. In the next part of this series, we’ll discuss issues related to deserializing data, loading yaml configurations, information leakage, and more.

Thanks to Zach Schipono and Carissa Sandoval for reviewing drafts of this.