I had a chat with an engineer who joined a new company and well-established team. They felt uneasy offering feedback during design and code reviews to the other engineers and second-guessed each comment. What feedback could they offer to a team that knows what they’re doing? Haven’t the other engineers already considered any points they might bring up?

I experience this too when I join new teams. I have a hard time figuring out how to engage and what I can offer. In this post, we’ll look at possible causes and steps to become more comfortable with giving feedback.

Let’s start with causes. In my experience, discomfort comes from:

- Venn diagram knowledge

- New environments

- Impostor syndrome

Venn diagram knowledge

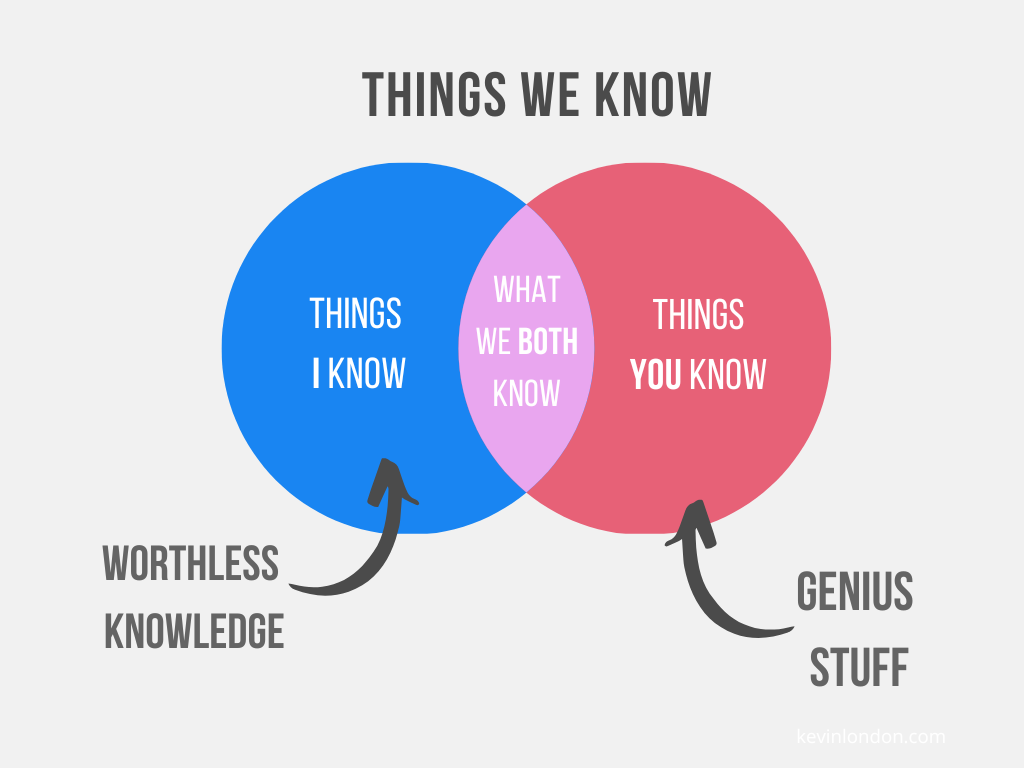

Sometimes when I talk with someone, I’m blown away by how much they know. How did they learn so much? I start to doubt myself. It helps me to frame knowledge as like a Venn diagram, where we each have an area that covers what we know. Here’s an illustration of how I think about it:

Encountering someone with a wildly different Venn diagram coverage circle can feel like meeting a genius. It doesn’t necessarily mean they know more than us, just that we have different areas that we know. As we learn more, our knowledge circle shifts and grows.

In the diagram, I label what I know as “worthless knowledge”. I think it’s common to discount what we’ve learned. If you can, try to appreciate what you already know and that others might be as impressed by what you’ve learned.

New Environments

When joining a team, or when there’s no process, it’s challenging to know what to do. Why do we do things the way that we do? Should I suggest something different? How long should I wait before I try to change the process?

Dan Luu wrote a post on the Normalization of Device, where he talks about the process of strange things becoming normal over time and how that happens. From his post:

People don’t automatically know what should be normal, and when new people are onboarded, they can just as easily learn deviant processes that have become normalized as reasonable processes.

Julia Evans described to me how this happens:

- new person joins

- new person: WTF WTF WTF WTF WTF

- old hands: yeah we know we’re concerned about it

- new person: WTF WTF wTF wtf wtf w…

- new person gets used to it

- new person #2 joins

- new person #2: WTF WTF WTF WTF

- new person: yeah we know. we’re concerned about it.

So as a new person, when is it right to act on these WTF impulses? It’s hard to know! This can lead to feeling uncertain about when to offer an opinion and it’s normal to experience in new environments.

Impostor Syndrome

When I make a change such as switching companies, teams, or even projects, I feel dread. Will my colleagues see that I’m figuring it out as I go and I don’t have the answers? Will this be the time I’m found out as a fraud? Will they judge me for not measuring up to their expectations or skill?

These feelings may come from “impostor syndrome”. Psychology Today defines says:

People who struggle with impostor syndrome believe that they are undeserving of their achievements and the high esteem in which they are, in fact, generally held. They feel that they aren’t as competent or intelligent as others might think—and that soon enough, people will discover the truth about them.

I’ve written more about impostor syndrome and go back to it when I’m feeling underwater.

Overcoming

One strategy for overcoming these uncomfortable feelings is by paying attention to them. When I’m starting negative self-talk or feeling anxious, noticing it can help me take steps to fix it. Catching the start of a loop or falling into a pattern can prevent thought loops.

Ask Open-Ended Questions

One technique I’ve found helpful for offering feedback is to approach discussions through exploration instead of recommendation.

Perhaps I’m reviewing a design document and notice there’s no client-side cache. I’m concerned about request latency. Here’s a few ways I could comment:

- Recommending: “I’d use a distributed cache like Redis here to speed up requests.”

- Exploring: “What latency requirements do we have? What options can we use if we’re not meeting our service expectations?”

In the recommending example, I’m making a few assumptions:

- The service or implementation isn’t going to meet its latency requirements

- Using a distributed cache will improve it

- This specific technology is the right one to pick

- My way is the right way

But maybe you looked into this! Maybe the service isn’t latency sensitive and it’s ok if it takes a little longer to resolve a request. When I explore, I hope to learn.

I’ve written about code reviews and offering feedback before if you’d like to read more. Julia Galef wrote The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don’t which has concrete suggestions for changing approach too.

Be Kind to Future-You

Imagine that you’re in an on-call rotation and your pager wakes up everyone in the house at 3 AM. You acknowledge the page and open your computer. How much mental processing will you be capable of under those conditions? How will you figure out what went wrong?

Another lens: In 6 months, will what’s under review still make sense? I’ve lost count of times I’ve looked at code, wondered who wrote it because it caused a bug or I had a hard time understanding it, and it turned out to be something I wrote.

This is all to say that offering feedback now can help make what’s still under construction easier to reason and think about, which makes it easier to fix or maintain even under duress.

I love receiving comments and questions on code reviews or design documents. I treat it as signal that I could better express myself and make it easier to understand.

Feedback as Growth

Much of my growth and career development has come from offering and receiving feedback from others. I cannot overstate how much it’s helped me. I still learn from my colleague’s comments and I’m grateful we’re working together to build better systems and software for our customers.

I want to receive hear from newer engineers if there’s something we could improve or is unclear! In Mindfulness in Plain English, there’s a section that comes to mind:

We all have blind spots. The other person is our mirror for us to see our faults with wisdom. We should consider the person who shows our shortcomings as one who excavates a hidden treasure in us that we were unaware of. It is by knowing the existence of our deficiencies that we can improve ourselves… . Before we try to surmount our defects, we should know what they are.

… If we are blind to our own flaws, we need someone to point them out to us. When they point out our faults, we should be grateful to them like the Venerable Sariputta, who said: “Even if a seven-year-old novice monk points out my mistakes, I will accept them with utmost respect for him.”

Everyone has areas they can work on to improve and I think those new to the team have a valuable and unique perspective. Even though it feels uncomfortable to offer feedback to others, it offers an invaluable opportunity to grow.

With that, I hope you feel a little better about offering feedback to other engineers. Please let me know if you have any other suggestions that work for you.